Suicide is a pressing public health concern in Canada, and it’s deeply troubling to know that close to 75% of the estimated 4,000 suicide deaths each year are men. This trend has persisted over the last four decades, making it crucial to understand the underlying factors contributing to this alarming statistic.

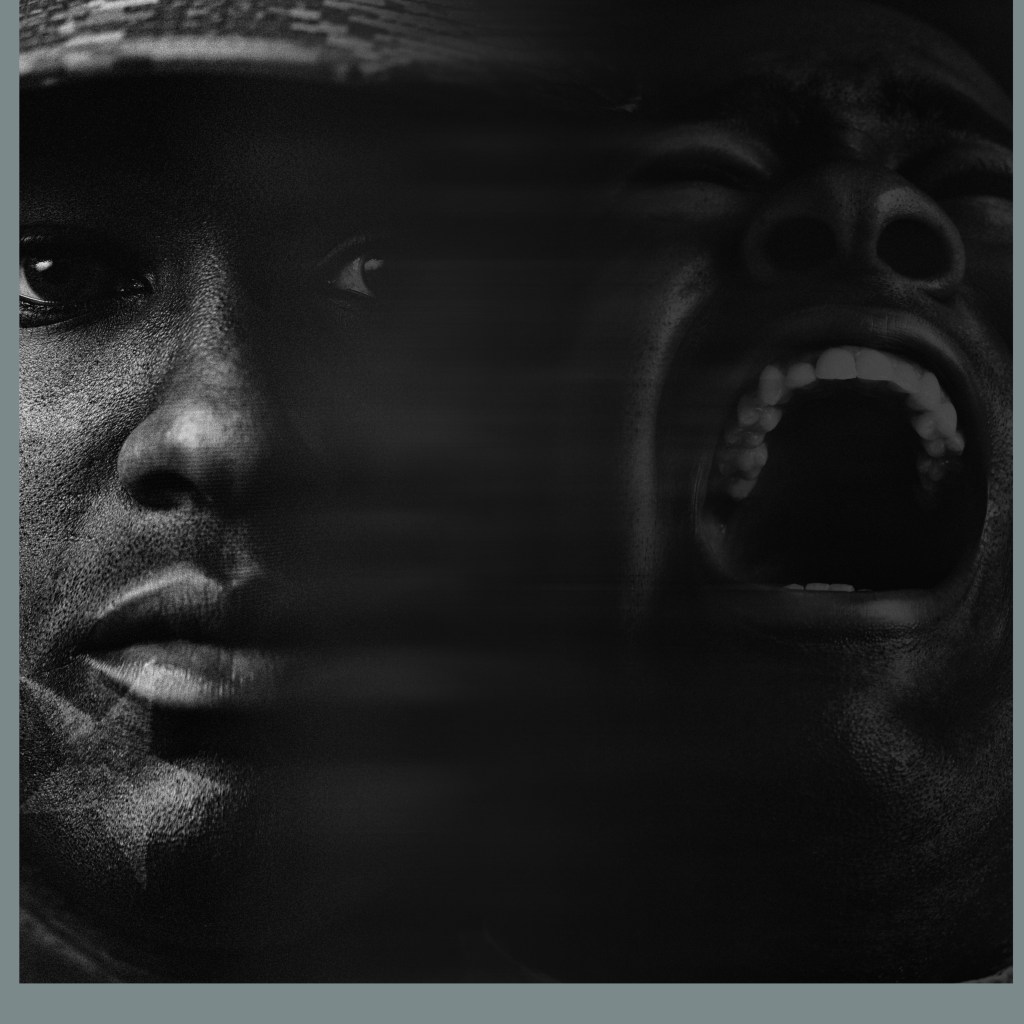

One notable aspect researchers have uncovered is the “gender paradox.” While men are more likely to die by suicide, women are more likely to attempt it. This paradox reflects how societal expectations and gender norms can impact men’s mental health, causing them to suffer silently and avoid seeking help when needed.

Breaking Down the Factors Impacting Men’s Mental Health and Suicidal Risk:

1. Population Diversity: Canada is a culturally rich nation, with over 38 million inhabitants from diverse backgrounds. Nearly 50% of the population consists of men, and racialized groups comprise around a quarter of the country’s population. Moreover, more than 800,000 individuals identify as Indigenous men, and approximately 380,000 men identify as 2SLGBTQ+. Each of these groups may face unique challenges and vulnerabilities that affect their mental health.

2. High-Risk Groups: Within the male population, Indigenous men and sexual and gender minority men are at the highest risk for suicide. Indigenous men exhibit higher rates of suicidal behavior, with suicide attempts among male Inuit youth being ten times higher compared to non-Indigenous male youth. Sexual minority men, such as gay, bisexual, or queer men, are also up to six times as likely to experience suicidal ideation.

3. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing risk factors for suicide in men, including psychological distress, job loss, loneliness, and problematic alcohol and substance use. Those living in marginalized conditions, such as Indigenous men and sexual and gender minority men, have reported increased struggles with alcohol and cannabis use, depression, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts.

Strategies to Reduce the Risk of Suicide

1. Challenging Traditional Masculine Norms: Society often pressures men to uphold certain masculine norms, such as being strong, self-reliant, and stoic. These expectations can hinder men from seeking help for mental health issues, fearing that it might be seen as a sign of weakness. By challenging these norms and promoting open discussions about emotions and mental well-being, we can create a safer space for men to seek help.

2. Addressing Problematic Alcohol Use: Problematic alcohol consumption, which is more prevalent among men, can exacerbate depressive symptoms and increase the risk of suicide. By increasing awareness and promoting safer alcohol consumption, we can mitigate these risks.

3. Recognizing Signs of Depression: Depression can manifest differently in men compared to women, with increased irritability, anger, impulsivity, and substance use. Recognizing these signs can help identify men who may be at risk of suicide.

4. Combating Social Isolation: Social connections are essential for mental well-being, and supporting men during challenging life events, such as relationship breakdowns, can help combat social isolation.

5. Addressing Societal Stigma and Trauma: Various life experiences and identities can impact men’s mental health and access to support services. It’s crucial to provide inclusive resources and services that consider diverse experiences and backgrounds.

Our Collective Responsibility

Men’s mental health and suicide prevention in Canada require collective action and understanding. By challenging harmful gender norms, promoting mental health awareness, and providing accessible and inclusive support, we can create an environment where men feel comfortable seeking help when they need it most.

Remember, it’s essential to be there for one another, lend a listening ear, and encourage open conversations about mental health. Together, we can support our brothers and make a meaningful impact on men’s mental well-being, reducing the devastating toll of suicide in our communities.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts or mental health issues, it is crucial to seek help promptly. There are various resources available in Canada to provide support and assistance:

- Crisis Services Canada: 1-833-456-4566 (available 24/7) or text 45645 (available from 4 p.m. to midnight ET).

References

Amiri, S. (2020). Prevalence of suicide in immigrants/refugees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 11, 1-36. https://doi.org /10.1080/13811118.2020.1802379

Boden, J. M., & Fergusson, D. M. (2011). Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106(5), 906-914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x

Canetto, S. S., & Sakinofsky, I. (1998). The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 28(1), 1-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/11102320/

Canadian Mental Health Association, University of British Columbia, Mental Health Foundation, The Agenda Collaborative, & Maru/Matchbox. (n.d.). Mental health impacts of COVID-19: Wave 2. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2020/12/CMHA-UBC-wave-2-Summary-of-Findings-FINAL-EN.pdf

Cavanagh, J. T. O., Carson, A. J., Sharpe, M., & Lawrie, S. M. (2003). Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 33(3), 395405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006943

Centre for Mental Health and Addiction (CAMH). (2021). COVID-19 national survey dashboard. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-andcovid-19/covid-19-national-survey

Canadian Mental Health Association, University of British Columbia, Mental Health Foundation, The Agenda Collaborative, & Maru/Matchbox. (n.d.). Mental health impacts of COVID-19: Wave 2. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2020/12/CMHA-UBC-wave-2-Summary-of-Findings-FINAL-EN.pdf

Crawford, A., (2016). Suicide among Indigenous peoples in Canada. In The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Ernst, M., Klein, E. M., Beuteal, M. E., & Bräler, E. (2021). Gender-specific associations of loneliness and suicidal ideation in a representative population sample: Young, lonely men are particularly at risk. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.085

Evans, R., Scourfield, J., & Moore, G. (2016). Gender, relationship breakdown, and suicide risk: A review of research in Western countries. Journal of Family Issues, 37(16), 2239-2264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14562608

Fast, E., & Collin-Vèzina, D. (2019). Historical trauma, race-based trauma, and resilience of Indigenous peoples: A literature review. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 14(1), 166-181. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069069ar

Ferlatte, O., Oliffe, J. L., Salway, T., Broom, A., Bungay, V., & Rice, S. (2019). Using photovoice to understand suicidality among gay, bisexual, and two-spirit men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(5), 1529-1541. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10508-019-1433-6

Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Hankivsky, O., Trussler, T., Oliffe, J. L., & Marchand, R. (2018). Recent suicide attempts across multiple social identities among gay and bisexual men: An intersectionality analysis. Journal of Homosexuality

Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Oliffe, J. L., Kia, H., Rice, S., Morgan, J., Lowik, A. J., & Knight, R. (2019). Sexual and gender minorities’ readiness and interest in supporting peers experiencing suicide-related behaviors. Crisis, 41(4), 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000632

Goodwill, et al. (2021). Everyday discrimination, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation among African American men. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13811118.2019.1660287

Jenkins, E. K., McAuliffe, C., Hirani, S., Richardson, C., Thomson, K. C., McGuinness, L., Morris, J., Kousoulis, A., & Gaermann, A. (2021). A portrait of the early and differential mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Findings from the first wave of a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Preventive Medicine, 145, Article 106333. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106333

Kaplan, M. S., McFarland, B. H., Huguet, N., Conner, K., Caetano, R., Giesbrecht, N., & Nolte, K. B. (2013). Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: A gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. BMJ Injury Prevention, 19(1), 38-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ injuryprev-2012-040317

Kumar, M. B., & Tjepkema, M. (2019). Suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011-2016): Findings from the 2011 Canadian census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC). Statistics Canada. Consumer Policy Research Database. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/99-011-x/99-011- x2019001-eng.htm

Milner, A., Shields, M., & King, T. (2019). The influence of masculine norms and mental health on health literacy among men: Evidence from the ten to men study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(5), 1-9. https://doi. org/10.1177/1557988319873532

Nurmi, M. A., Mackenzie, C. S., Roger, K., Reynolds, K., & Urquhart, J. (2018). Older men’s perceptions of the need for and access to male-focused community programmes such as Men’s Sheds. Ageing and Society, 38(4), 794-816. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16001331

Oliffe, J. L., Kelly, M. T., Gonzales Montaner, G., Links, P. S., Kealy, D., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2021). Segmenting or summing the parts? A scoping review of male suicide research in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 66(5), 433-445. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437211000631

Oliffe, J. L., Hannah-Leith, M. N., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Black, N., Mackenzie, C., Lohan, M, & Creighton, G. (2016). Men’s depression and suicide literacy: A nationally representative Canadian survey. Journal of Mental Health, 25(6), 520-526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1177770

Oliffe, J. L., Kelly, M. T., Gonzales Montaner, G., Links, P. S., Kealy, D., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2021). Segmenting or summing the parts? A scoping review of male suicide research in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 66(5), 433-445. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437211000631

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020). Suicide in Canada: Key statistics [Infographic]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/ publications/healthy-living/suicide-canada-key-statistics-infographic.html

Rehm, J., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

Richardson, C., Robb, K. A., & O’Connor, R. C. (2021). A systematic review of suicidal behaviour in men: A narrative synthesis of risk factors. Social Science and Medicine, Article 113831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113831

Salami, B., Salma, J., & Hegadoren, K. (2019). Access and utilization of mental health services for immigrants and refugees: Perspectives of immigrant service providers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 152-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12512

Sanchez, T. H., Zlotorzynska, M., Rai, M., & Baral, S. D. (2020). Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April. AIDS and Behavior, 24(7), 2024-2032. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10461-020-02894-2

Seidler, Z. E., Dawes, A. J., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2016). The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 106-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cpr.2016.09.002

Sørensen, E. H., Thorgaard, M. V., & Østergaard, S. D. (2020). Male depressive traits in relation to violent suicides or suicide attempts: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262, 55-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jad.2019.10.054

Statistics Canada. (2022). Population estimates, quarterly (Table 17-10-0009- 01). Retrieved Feb. 7, 2022, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/ tv.action?pid=1710000901 6. Statistics Canada. (2021). Census profile, 2016 census. https://tinyurl. com/2p8nkzth

Statistics Canada. (2022). Population estimates, quarterly (Table 17-10-0009- 01). Retrieved Feb. 7, 2022, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/ tv.action?pid=1710000901 6. Statistics Canada. (2021). Census profile, 2016 census. https://tinyurl. com/2p8nkzth

Statistics Canada. (2020, May 8). Labour Force Survey, April 2020. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200508/dq200508a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2021, June 15). A statistical portrait of Canada’s diverse LGBTQ+ communities. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/dailyquotidien/210615/dq210615a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2017). Health indicators, by Aboriginal identity, age-standardized rates, four-year period estimates (Table 13-10-0458-01). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310045801

Struszczyk, S., Galdas, P. M., & Tiffin, P. A. (2019). Men and suicide prevention: A scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(1), 80-88. https://doi.org/10.108 0/09638237.2017.1370638 21. Oliffe, J. L., Rossnagel, E., Seidler, Z. E., Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Men’s depression and suicide [Review]. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(10), 103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1088-y

Varin, M., Orpana, H. M., Palladino, E., Pollock, N. J., & Baker, M. M. (2021). Trends in suicide mortality in Canada by sex and age group, 1981 to 2017: A population-based time series analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 66(2), 170-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720940565

Vogel, D. L., & Heath, P. J. (2016). Men, masculinities, and help-seeking patterns. In Y. J. Wong & S. R. Wester (Eds.), APA handbook of men and masculinities (pp. 685-707). American Psychological Association.

Whitley, R. (2018). Men’s mental health: Beyond victim-blaming. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(9), 577-580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718758041

Yip, P. S. F., Yousuf, S., Chan, C. H., Yung, T., & Wu, K. C.-C. (2015). The roles of culture and gender in the relationship between divorce and suicide risk: A meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 128, 87-94. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.034